“Four Essays on Christian Liberalism” by Dionisije Dejan Nikolić is not without a certain, not at all accidental (albeit polemical) collusion with the work of (it is to be hoped) the blessedly departed Mr. Isaiah Berlin: “Four Essays on Freedom”.

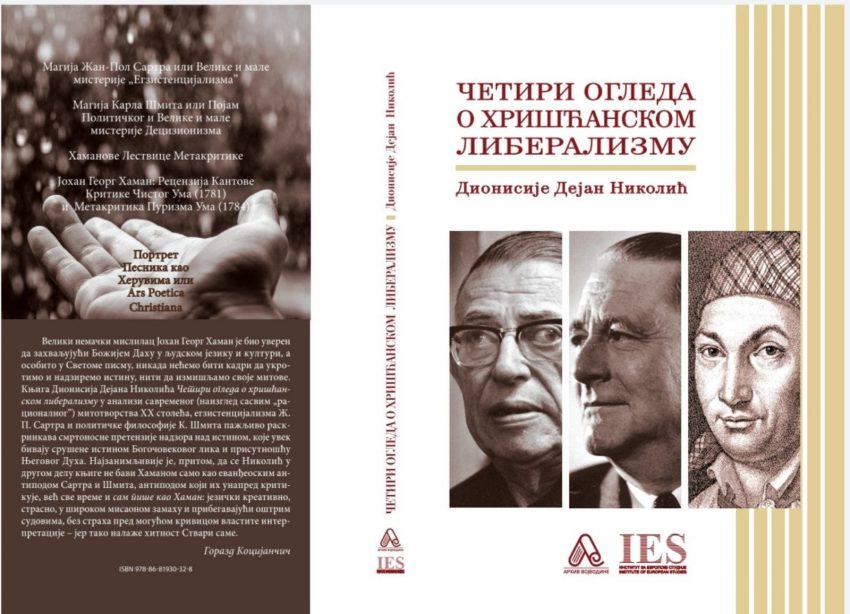

In brief, in the first three essays the author dealt with the three colors of Leviathan: in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Magic with red, in Carl Schmidt’s Magic with black, and in Hamann’s Ladders of Metacriticism with Immanuel Kant’s Magic, i.e. with the yellow color of Leviathan (which in LGBT and New Age variants can also be of rainbow colors).

The theme of the fourth essay, Portrait of the Poet as a Cherub or Ars Poetica Christiana is: how to appease, quiet down or transform Leviathan, i.e. the Seal of the Eighth Day: The Uncreated Golden Light of True Freedom of Brotherhood and Unity in Christ.

Just like with Berlin, with Nikolić we have both negative and positive freedom: both freedom from and freedom for: freedom from sin and death, and freedom for deification and eternal life – in which, as it is written, everything we wish will be possible for us, that is: Maximum Liberalism without borders.

Moreover: since the saved, i.e. fully deified gods will be by grace not only infinite but also beginningless (anarchon): we also have the Maximum of Anarchism without limits. In nuce: the author explicates the spiritual-political theory of Orthodox Anarcholiberalism, considering it to be an important item in the Cultural and Spiritual War that is being waged for every word, concept, category, expression and term – among other things.

Nikolić therefore consistently insists on the difference between true and false enlightenment. He shows that actually Haman, not Kant, was a real enlightener, and a radical enlightener: precisely in the sense of Orthodox anthropological maximalism, in which enlightenment (photosis) is deification (theosis): to be truly enlightened means to become a god by grace.

What is it, the author asks, enlightenment, if not the maturity for Exodus from the self-concealed hubris of autonomy: through purification, conversion, enlightenment and deification, and Entering through theanthroponomy into the House of the Father of Light. What is enlightenment, if not the maturity to be like children, brought up for learned admiration (docta admiratio)?

These Essays are interspersed with a multitude of interesting and exciting thematizations, which can be amusing, and certainly instructive and stimulating, even for readers without any major experience in philosophical and theological readings. And such, but even trained specialists, will find out why are the figures of Agrippa’s Trilemma and Plato’s Peritrope so important, what is the difference between nihilism and nemoism, what did Sartre try to hide from his readers, is Schmitt’s concept of the political a concept at all, from which authors did Hume copy “his” ideas that made him famous, whether and when did Kant started to believe for himself to be God, who was Goethe’s and Kierkegaard’s most important teacher who refused to write Physics for Children together with Kant, why Kant was called the Beast from Königsberg, whether and why Mallarmé was in love with nothingness, how Guillaume Apollinaire defended Serbian Cyrillic, why Tzara and Breton hated Baudelaire and Rimbaud, in which the Elder Porphyry Kavsokalyvit and Ernst Jinger agreed, and much more…

The book also contains two very valuable contributions, namely Nikolić’s first and so far the only translation from German into Serbian of the famous metacritical studies of Johann Georg Hamann. These are the Review of Kant’s Critique of the Pure Reason (1781) and the Metacriticism of the Purism of the Reason (1784).

The reviewers are Dr. Aleksandar Stevanović and Dr. Aleksandar Gajić, and the author of the afterword and special recommendation is Gorazd Kocijančič.